Difference between revisions of "Ancient Rome"

m |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{X}} | |

| + | [[Image:Forum Romanum panorama 2.jpg|thumb|right|400px|The [[Roman Forum]] was the central area around which ancient Rome developed.]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | |

| + | '''Ancient Rome''' was a [[civilization]] that grew out of the [[city-state]] of [[Rome]], founded on the [[Italian peninsula]] in the [[8th century BCE]]. During its twelve-century existence, the Roman civilization shifted from a [[monarchy]] to an [[oligarchy|oligarchic]] [[republic]] to a vast [[empire]]. It came to dominate [[Western Europe]] and the entire area surrounding the [[Mediterranean Sea]] through [[conquest]] and [[assimilation]], but eventually succumbed to barbarian invasions in the [[5th century]], marking the [[decline of the Roman Empire]] and the beginning of the [[Middle Ages]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Roman civilization is often grouped into "[[classical antiquity]]" with [[ancient Greece]], a civilization that inspired much of the [[culture of ancient Rome]]. Ancient Rome contributed heavily to the development of law, war, art, literature, architecture, and language in the [[Western world]], and its [[history of Rome|history]] continues to have a major influence on the world today. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| + | ''Main Article '''[[History of Rome]]''' and '''[[Timeline of ancient Rome]]''''' | ||

===Monarchy=== | ===Monarchy=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:She-wolf suckles Romulus and Remus.jpg|thumb|right|300px|According to legend, [[founding of Rome|Rome was founded]] in [[750s BC|753 BC]] by [[Romulus and Remus]], who were raised by a she-wolf.]] | |

| − | [[Image: | ||

| − | + | ''Main Article '''[[Roman Kingdom]]''''' | |

| − | + | The city of [[Rome]] grew from settlements around a ford on the river [[Tiber]], a crossroads of traffic and trade. According to [[archaeology|archaeological]] evidence, the village of Rome was probably founded sometime in the [[9th century BC]] by members of two central Italian tribes, the [[Latins]] and the [[Sabine]]s, on the [[Palatine Hill|Palatine]] and [[Quirinal Hill|Quirinal]] Hills. The [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscans]], who had previously settled to the north in [[Etruria]], seem to have established political control in the region by the late [[7th century BC]]. The Etruscans apparently lost power in the area by the late [[6th century BC]], and at this point, the original Latin and Sabine tribes reinvented their government by creating a republic, with much greater restraints on the ability of rulers to exercise power. | |

| + | |||

| + | In Roman legend, Rome was [[founding of Rome|founded]] on [[April 21]], [[750s BC|753 BC]] by twins descendents of the [[Troy|Trojan]] prince [[Aeneas]], [[Romulus and Remus]]. Romulus, whose name inspired the name ''Rome'', killed Remus in a quarrel over where their new city would be located, and became the first of seven [[Roman Kingdom|Kings of Rome]].{{ref|Livy1}} | ||

===Republic=== | ===Republic=== | ||

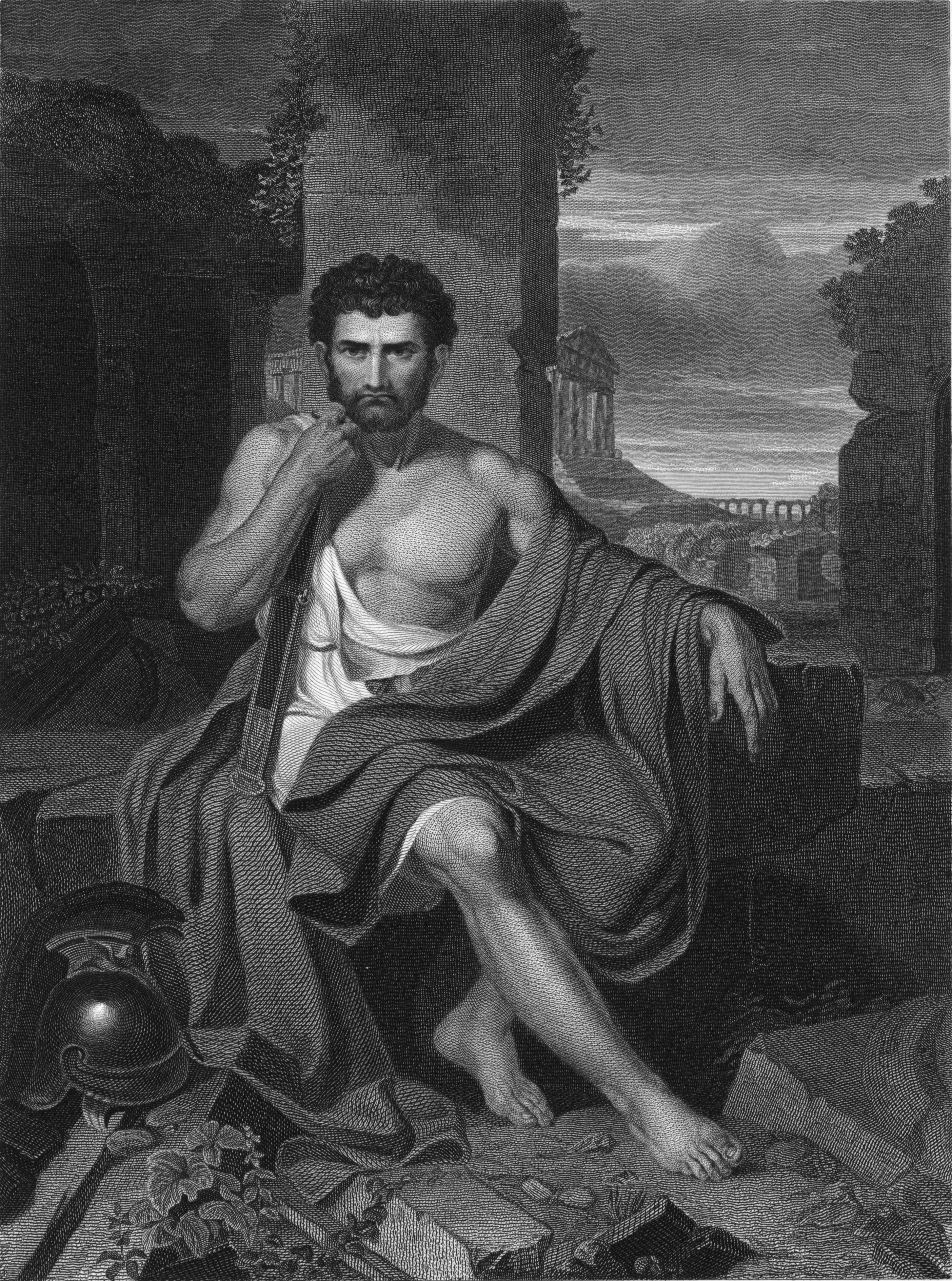

| − | + | [[Image:Marius Carthage.jpg|frame|left|[[Marius]], a Roman general and politician who dramatically reformed the [[Military history of the Roman Empire|Roman military]].]] | |

| − | [[Image: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Roman Republic]] was established around [[510 BC]], according to later writers such as [[Livy]], when the last of the seven king of Rome, [[Lucius Tarquinius Superbus|Tarquin the Proud]], was deposed, and a system based on annually-elected [[magistratus|magistrates]] was established. The most important magistrates were the two [[consul]]s, who together exercised executive authority, but had to contend with the [[Roman Senate|Senate]], which grew in size and power with the establishment of the Republic. The magistracies were originally restricted to the elite [[patrician]]s, but were later opened to common people, or [[plebs]].{{ref|Livy2}} | |

| − | + | The Romans gradually subdued the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the Etruscans. The last threat to Roman [[hegemony]] in Italy came when [[Taranto|Tarentum]], a major [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] colony, enlisted the aid of [[Pyrrhus of Epirus]] in [[282 BC]], but this effort failed as well. The Romans secured their conquests by founding Roman colonies in strategic areas, and established stable control over the region.{{ref|Tuomisto1}} In the second half of the [[3rd century BC]], Rome clashed with [[Carthage]] in the first two [[Punic wars]]. These wars resulted in Rome's first overseas conquests, of [[Sicily]] and [[Hispania]], and the rise of Rome as a significant imperial power. After defeating the [[Macedon]]ian and [[Seleucid Empire]]s in the [[2nd century BC]], the Romans became the masters of the [[Mediterranean Sea]].{{ref|Bagnall}} | |

| − | + | But foreign dominance led to internal strife. Senators became rich at the provinces' expense, but soldiers, mostly small farmers, were away from home longer and could not maintain their land, and the increased reliance on foreign [[slavery in antiquity|slaves]] reduced the availablility of paid work. The Senate squabbled perpetually, repeatedly blocking important land reforms. Violent gangs of the urban unemployed, controlled by rival Senators, intimidated the electorate by violence. The denial of [[Roman citizen|Roman citizenship]] to allied Italian cities led to the [[Social War]] of [[91 BC|91]]-[[88 BC]]. The military reforms of [[Marius]] resulted in soldiers often having more loyalty to their commander than to the city, and a powerful general could hold the city and Senate ransom. This culminated in [[Lucius Cornelius Sulla|Sulla]]'s brutal [[Roman dictator|dictatorship]] of [[81 BC|81]]-[[79 BC]]. {{ref|Scullard1}} | |

| − | + | In the mid-[[1st century BC]], three men, [[Julius Caesar]], [[Pompey]], and [[Marcus Licinius Crassus|Crassus]], formed a secret pact—the [[First Triumvirate]]—to control the Republic. After Caesar's [[Gallic Wars|conquest of Gaul]], a stand-off between Caesar and the Senate led to [[Caesar's civil war|civil war]], with Pompey leading the Senate's forces. Caesar emerged victorious, and was made [[Roman dictator|dictator]] for life.{{ref|meier}} In [[42 BC]], Caesar was assassinated by senators fearing that Caesar sought to restore the monarchy, and a [[Second Triumvirate]], consisting of Caesar's designated heir, [[Augustus]], and his former supporters, [[Mark Antony]] and [[Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (triumvir)|Lepidus]], took power. However, this alliance too soon descended into a struggle for dominance. Lepidus was exiled, and when Augustus defeated Antony and [[Cleopatra VII of Egypt|Cleopatra]] of [[Egypt]] at the [[Battle of Actium]] in [[31 BC]], he became the undisputed ruler of Rome. {{Ref|Scullard2}} | |

===Empire=== | ===Empire=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Roman_Empire_Map.png|thumb|right|350px|The [[Roman Empire]] reached its greatest extent under [[Trajan]].]] | |

| − | |||

| − | [[Image: | ||

| − | + | With his enemies defeated, [[Augustus]] assumed almost absolute power, retaining only the pretense of the Republican form of government. His designated successor, [[Tiberius]], took power without bloodshed, establishing the [[Julio-Claudian dynasty]], which lasted until the death of [[Nero]] in [[69]]. The territorial expansion of what was now the [[Roman Empire]] continued, and the state remained secure, despite a series of emperors widely viewed as depraved and corrupt. Their rule was followed by the [[Flavian dynasty]].{{ref|suetonius}} During the reign of the "[[Five Good Emperors]]" ([[96]]–[[180]]), the Empire reached its territorial, economic, and cultural zenith. The state was secure from both internal and external threats, and the Empire prospered during the [[Pax Romana]] ("Roman Peace"). With the conquest of [[Dacia]] during the reign of [[Trajan]], the Empire reached the peak of its territorial expansion; Rome's dominion now spanned 2.5 million square miles.{{ref|Atlas1}} | |

| − | + | The period between [[180]] and [[235]] was dominated by the [[Severan dynasty]], and saw several incompetent rulers, such as [[Elagabalus]]. This and the increasing influence of the army on imperial succession led to a long period of imperial collapse known as the [[Crisis of the Third Century]]. The crisis was ended by the more competent rule of [[Diocletian]], who in [[293]] divided the Empire into [[Tetrarchy|four parts]] ruled by two co-emperors. The various co-rulers of the Empire competed and fought for supremacy for more than half a century. In [[330]], Emperor [[Constantine I (emperor)|Constantine I]] moved the capital of the Roman Empire to [[Byzantium]], and the Empire was permanently divided into the eastern [[Byzantine Empire]] and the [[Western Roman Empire]] in [[364]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The Western Empire was constantly harassed by barbarian invasions, and the gradual [[decline of the Roman Empire]] continued over the centuries. In [[410]], the city of Rome itself was sacked, and in [[September 4]], [[476]], the Germanic chief [[Odoacer]] forced the last Roman emperor in the west, [[Romulus Augustus]], to abdicate. Having lasted for approximately 1200 years, the rule of Rome in the west came to an end. | |

| − | + | ==Society== | |

| + | Life in ancient Rome revolved around the city of [[Rome]], located on [[Seven hills of Rome|seven hills]]. The city had a vast number of [[monument|monumental]] [[structure]]s like the [[Colosseum]], the [[Forum of Trajan]] and the [[Pantheon, Rome|Pantheon]]. It had [[fountains]] with fresh drinking-water supplied by hundreds of miles of [[aqueducts]], [[Roman theatre (structure)|theater]]s, [[gymnasium (ancient Greece)]]s, [[thermae|bath complexes]] complete with [[libraries]] and shops, marketplaces, and functional sewers. Throughout the territory under the control of ancient Rome, [[residential]] [[architecture]] ranged from very modest [[house]]s to [[Roman_villa|country villas]], and in the [[capital city]] of Rome, there were [[imperial]] [[residence]]s on the elegant [[Palatine Hill]], from which the word "''palace''" is derived. The poor lived in the city center, packed into [[apartment]]s, which were almost like modern [[ghetto]]s. | ||

| − | + | The city of Rome was the largest urban center of that time, with a population well in excess of one million people, with some high-end estimates of 3.5 million and low-end estimates of 450,000. The public spaces in Rome resounded with such a din of hooves and clatter of iron [[chariot]] wheels that [[Julius Caesar]] had once proposed a ban on chariot traffic at night. Historical estimates indicate that around 30 percent of population under the jurisdiction of the ancient Rome lived in innumerable urban centers, with population of 10,000 and more and several military settlements, a very high rate of urbanization by pre-industrial standards. Most of these centers had a [[Roman Forum|forum]] and temples and same type of buildings, on a smaller scale, as found in Rome. | |

| − | : | + | ===Government=== |

| + | [[Image:Julius caesar.jpg|thumb|left|180px|[[Julius Caesar]]'s rise to power and assassination set the stage for [[Augustus]] to establish himself as the first ''[[imperator]]''.]] | ||

| − | + | Initially, Rome was ruled by elected [[Roman Kingdom|kings]]. The exact nature of the king's power is uncertain; he may have held near-absolute power, or may also have merely been the chief executive of the Senate and the people. At least in military matters, the king's authority (''[[imperium]]'') was likely absolute. He was also the head of the [[Roman religion|state religion]]. In addition to the authority of the King, there were three administrative assemblies: the [[Roman Senate|Senate]] acted as an advisory body for the King, the [[Curiate Assembly]] could pass laws suggested by the King, and the [[Comitia Calata]] was mainly an assembly of the people to bear witness to certain acts and hear proclamations. | |

| − | {{ | + | The class struggles of the [[Roman Republic]] resulted in an unusual mixture of [[democracy]] and [[oligarchy]]. Roman laws traditionally could only be passed by a vote of the Popular assembly. Likewise, candidates for public positions had to run for election by the people. However, the [[Roman Senate]] represented an oligarchic insitution, which acted as an advisory body.{{ref|Tuomisto2}} In the Republic, the Senate held great authority (''auctoritas''), but no actual legislative power (''[[imperium]]''). However, as the senators were individually very influential, it was difficult to accomplish anything against the collective will of the Senate. New Senators were chosen from among the most accomplished citizens by [[censor]]s, who could also remove a senator from his office if he was found morally corrupt. Later, [[quaestor]]s were also made automatic members of the Senate. |

| − | + | The Republic had no fixed bureaucracy, and only collected war taxes. Private citizens aspiring to high office largely paid for public works. In order to prevent any citizen from gaining too much power, new [[magistrate]]s were elected annually and had to share power with a colleague. For example, under normal conditions, the highest authority was held by two [[consul]]s. In an emergency, a temporary [[Roman dictator|dictator]] could be appointed.{{ref|Tuomisto3}} Throughout the Republic, the administrative system was revised several times to comply with new demands. In the end, it proved inefficient for controlling the ever-expanding dominion of Rome, contributing to the establishment of the [[Roman Empire]]. | |

| − | + | In the early Empire, the pretense of a republican form of government was maintained: the [[Roman Emperor]] was portrayed as only a ''[[princeps]]'', or "first citizen", and the Senate retained a degree of influence. However, the rule of the emperors became increasingly autocratic over time, and the Senate was reduced to an advisory body appointed by the emperor. The Empire did not inherit a set bureaucracy from the Republic, since the Republic did not have any permanent governmental structures apart from the Senate. The Emperor appointed assistants and advisors, but the state lacked many institutions, such as a centrally-planned budget. Some historians have cited this as a significant reason for the [[decline of the Roman Empire]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The territory of the Empire was divided into [[Roman province|provinces]]. The number of provinces increased with time, both as new territories were conquered and as provinces were divided into smaller units to discourage rebellions by powerful local rulers.{{ref|Atlas2}} Initially, the provinces were divided into imperial and senatorial provinces, depending on which institution had the right to select the governor. During the [[Tetrarchy]], the provinces of the empire were divided into 12 [[diocese]]s, each headed by a ''[[praetor|praetor vicarius]]''. The civilian and military authority were separated, with civilian matters still administred by the governor, but with military command transferred to a ''[[dux]]''. | |

| − | + | ===Law=== | |

| − | + | The roots to the legal principles and practices of the ancient may be traced to the law of the [[twelve tables]] (from [[449 BC]]) to the [[Corpus Iuris Civilis | codification]] of Emperor [[Justinian I]] (around [[530]]). the Roman law as preserved in Justinian's codes became the basis of legal principles and practices in the [[Byzantine Empire]], and in continental [[Western Europe]], and continued, in a broader sense, to be applied throughout most of Europe until the end of the [[18th century]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | '' | + | The major divisions of the law of the ancient Rome consisted of ''Ius Civile'', ''Ius Gentium'', and ''Ius Naturale''. The ''Ius Civile'' ("Citizen law") was the body of common laws that applied to Roman citizens and the [[Praetor#Praetor_Urbanus|''Praetores Urbani'']] (''sg. Praetor Urbanus'') were the individuals who had jurisdiction over cases involving citizens. The ''Ius Gentium'' ("Law of nations") was the body of common laws that applied to foreigners, and their dealings with Roman citizens. The [[Praetor#Praetor_Peregrinus|''Praetores Peregrini'']] ('' sg. Praetor Peregrinus'') were the individuals who had jurisdiction over cases involving citizens and foreigners. Ius naturale encompassed natural law, the body of laws that were considered common to all beings. |

| − | === | + | ===Economy=== |

| + | [[Image:Maximinus_denarius.jpg|left|frame|A [[Roman currency|Roman]] [[denarius]], a standardized [[silver]] coin.]] | ||

| − | + | Ancient Rome commanded a vast area of land, with tremendous natural and human resources available. As such, Rome's economy remained focused on [[agriculture]] and [[trade]]. Agricultural [[free trade]] changed the Italian landscape, and by the 1st century BC, vast grape and olive estates had supplanted the [[yeoman]] farmers, who were unable to match the imported grain price: the [[annexation]] of [[Egypt]], [[Sicily]] and [[Tunisia]] in [[North Africa]] provided a continuous supply of grains. In turn, [[olive oil]] and [[wine]] were Rome's main [[export]]s. Two-tier [[crop rotation]] was practiced, but farm productivity was overall low, around 1 ton per [[hectare]]. [[Industry|Industrial]] and [[manufacturing]] activities were relatively minimal, the largest such activity being the [[mining]] and [[quarrying]] of stones, which provided basic construction materials for the monuments of that period. | |

| − | The | + | The economy of the early Republic was largely based on smallholding and paid labour, but foreign wars and conquests made [[slavery in antiquity|slaves]] increasingly cheap and plentiful, and by the late Republic, the economy was largely dependent on slave labour for both skilled and unskilled work. Slaves are estimated to have constituted around 20% of Rome's population at this time. Only in the later Roman Empire did hired labour became more economical than slave ownership. |

| − | + | Although [[barter]] was common in ancient Rome, and often used in tax collection, Rome had a very developed [[coinage]] system, with [[brass]], [[bronze]], and [[precious metal]] coins in circulation throughout the Empire and beyond—some have even been discovered in [[India]]. Before the [[3rd century BC]], copper was traded by weight, measured in unmarked lumps, across central Italy. The original copper coins (''[[as (coin)|as]]'') had a face value of one [[Pound (weight)#Origins|Roman pound]] of copper, but weighed less. Thus, Roman money's utility as a unit of exchange consistently exceeded its [[intrinsic value]] as metal; after [[Nero]] began debasing the silver [[denarius]], its [[legal tender|legal]] value was an estimated one-third greater than its intrinsic. | |

| − | + | [[Horse]]s were too expensive, and other pack animals too slow, for mass trade on the [[Roman road]]s, which connected military posts rather than markets, and were rarely designed for wheels. As a result, there was little transport of [[commodity|commodities]] between Roman regions until the rise of [[Roman commerce#Sea routes|Roman maritime trade]] in the 2nd century BC. During that period, a trading vessel took less than a month to complete a trip from [[Gades]] to [[Alexandria]] via [[Ostia]], spanning the entire length of the [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]].{{ref|Atlas3}} Transport by sea was around 60 times cheaper than by land, so the volume for such trips was much larger. | |

| − | === | + | ===Class structure=== |

| + | [[Image:Toga Illustration.png|frame|right|A Roman clad in a [[toga]], the distinctive garb of Ancient Rome.]] | ||

| − | + | Roman society was strictly [[social hierarchy|hierarchical]], with [[slavery in antiquity|slaves]] (''servi'') at the bottom, [[freedman|freedmen]] (''liberti'') above them, and free-born citizens at the top. The free citizens were also divided by class. The broadest division was between the [[patrician]]s, who could trace their ancestry to the founding of the city, and the [[plebs|plebeians]], who could not. This became less important in the late Republic, as some plebeian families became wealthy and entered the ranks of the [[Roman Senate|Senate]], and some patrician families fell on hard times. In its place, the Roman elite were recognized for either their economic status—the [[equestrian (Roman)|equestrians]] (''equites''), wealthy businessmen—or their political status—the [[noble]]s (''nobiles''), who dominated the Senate. To be a noble, an individual needed to have a [[consul]] as an ancestor; men like [[Marius]] and [[Cicero]], who were the first of their families to rise to the consulship, were given the title ''[[novus homo]]'' ("new man"). | |

| − | + | Allied foreign cities were often given the [[Latin Right]], an intermediary level between full citizens and foreigners (''peregrini''), which gave their citizens rights under Roman law and allowed their leading magistrates to become full Roman citizens. Some of Rome's Italian allies were given full citizenship after the [[Social War]] of [[91 BC|91]]–[[88 BC]], and full Roman citizenship was extended to all free-born men in the Empire by [[Caracalla]] in [[212]]. | |

| − | === | + | ===Family=== |

| + | The basic units of Roman society were households and families. Household included the head of the household (''[[pater familias|paterfamilias]]''), his wife, children, and other relatives. In the upper classes, slaves and servants were also part of the household. The head of the household had great power (''patria potestas'', "father's power") over those living with him: He could force marriage and divorce, sell his children into slavery, claim his dependents' property as his own, and possibly even had the right to kill family members, although this has been recently disputed in academic circles. | ||

| − | + | ''Patria potestas'' even extended over adult sons with their own households: A man was not considered a ''paterfamilias'' while his own father lived. A daughter, when she married, usually fell under the authority of the ''paterfamilias'' of her husband's household, although this was not always the case, as she could choose to continue recognising her father's family as her true family. However, as Romans reckoned descent through the male line, any children she had would belong to her husband's family. | |

| − | + | Groups of related households formed a family ([[gens]]). Families were based on blood ties (or adoption), but were also political and economic alliances. Especially during the [[Roman Republic]], some powerful families, or ''[[Gens|Gentes Maiores]]'', came to dominate political life. | |

| − | + | [[Ancient Roman marriage]] was often regarded more as a financial and political alliance than as a romantic association, especially in the upper classes. Fathers usually began seeking husbands for their daughters when they reached an age between twelve and fourteen. The husband was almost always older than the bride. While upper class girls married very young, there is evidence that lower class women often married in their late teens or early twenties. {{ref|Johnston}} | |

| − | + | ===Education=== | |

| − | + | The goal of education in Rome was to make the students effective speakers. School started on March 24 each year. Every school day started in the early morning and continued throughout the afternoon. At first, boys were taught to read and write by their father, or by educated slaves, usually of Greek origin. Village schools were also established. Later, around [[200 BC]], boys and some girls were sent to schools outside the home around age 6. Basic Roman education included reading, writing, and counting, and their materials consisted of [[scroll (parchment)|scrolls]] and books. At age 13, students learned about [[Greek language|Greek]] and Roman literature and grammar in school. At age 16, some students went on to [[rhetoric]] school. Poorer people did not go to school, but were usually taught by their parents because school was not free. | |

| − | + | ===Language=== | |

| + | [[Image:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|left|thumb|250px|The language of Rome has had a profound impact on later cultures, as demonstrated by this [[Latin]] [[Bible]] from AD 1407.]] | ||

| − | + | The native language of the Romans was [[Latin]], an [[Italic languages|Italic language]] that relies little on [[word order in Latin|word order]], conveying meaning through a system of [[affix]]es attached to [[word stem]]s. Its alphabet, the [[Latin alphabet]], is ultimately based on the [[Greek alphabet]]. Although surviving [[Latin literature]] consists almost entirely of [[Classical Latin]], an artificial and highly stylized and polished [[literary language]] from the [[1st century BC]], the actual spoken language of the Roman Empire was [[Vulgar Latin]], which significantly differed from Classical Latin in grammar and vocabulary, and eventually in pronunciation. | |

| − | + | While Latin remained the main written language of the Roman Empire, [[Greek language|Greek]] came to be the language spoken by the well-educated elite, as most of the literature studied by Romans was written in Greek. In the eastern half of the Roman Empire, which became the [[Byzantine Empire]], Greek eventually supplanted Latin as both the written and spoken language. The expansion of the Roman Empire spread Latin throughout Europe, and over time Vulgar Latin evolved and [[dialect]]ized in different locations, gradually shifting into a number of distinct [[Romance language]]s. | |

| − | + | During the European [[Middle Ages]] and [[Early Modern period]], Latin maintained a role as western Europe's ''[[lingua franca]]'', an international language of [[academia]] and [[diplomacy]]. | |

| + | Eventually supplanted in this respect by [[French language|French]] in the [[19th century]] and [[English language|English]] in the [[20th century]], Latin continues to see heavy use in religious, legal, and scientific terminology. It has been estimated that 80% of all scholarly English words derive directly or indirectly from Latin. | ||

| − | + | Although Latin is an [[extinct language]] with very few remaining fluent speakers, [[Ecclesiastical Latin]] remains the traditional language of the [[Roman Catholic Church]] and the official language of [[Vatican City]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Art, literature and music=== | |

| + | [[Image:Cato.jpeg|thumb|200px|Roman sculpture was at its most original in the production of strongly characterized [[portraits]] such as this bust of [[Cato the Elder]].]] | ||

| − | + | Most early Roman painting styles show [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscan]] influences, particularly in the practice of political painting. In the 3rd century BC, Greek art taken as booty from wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists. Evidence from the remains at Pompeii shows diverse influence from cultures spanning the Roman world. Portrait sculpture during the period utilized youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism. During the Antonine and Severan periods, more ornate hair and bearding became prevalent, created with deeper cutting and drilling. Advancements were also made in relief sculptures, usually depicting Roman victories. | |

| − | |||

| − | Most | ||

| − | + | Roman literature was from its very inception influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest extant works are of historical epics telling the early military history of Rome. As the Republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy. | |

| − | + | ===Games and activities=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The ancient city of Rome had a place called Campus, a sort of drill ground for Roman soldiers, which was located near the River Tiber. Later, the Campus became Rome's track and field playground, which even Julius Caesar and Augustus were said to have frequented. Imitating the Campus in Rome, similar grounds were developed in several other urban centers and military settlements. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the campus, the youth assembled to play and exercise, which included jumping, wrestling, boxing and racing. Riding, throwing, and swimming were also preferred physical activities. In the countryside, pastime also included fishing and hunting. Women did not participate in these activities. Ball-playing was a popular sport, and ancient Romans had several ball games, which included Handball (Expulsim Ludere), field hockey, catch, and some form of Soccer. | |

| − | === | + | ===Religion=== |

| + | [[Image:Jupiter Tonans.jpg|thumb|left|200px|''Iuppiter Tonans'' ("[[Jupiter (god)|Jupiter]] the Thunderer"), a sculpture of the supreme Roman deity.]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | Archaic [[Roman mythology]], at least concerning the gods, was made up not of narratives, but rather of complex interrelations between gods and humans. Unlike in [[Greek mythology]], the gods were not personified, but were vaguely-defined sacred spirits called ''[[numina]]''. Romans also believed that every person, place or thing had its own ''[[genius (mythology)|genius]]'', or guardian spirit. During the [[Roman Republic]], [[Roman religion]] was organized under a strict system of priestly offices, of which the [[Pontifex Maximus]] was the most important. [[Flamen]]s took care of the cults of various gods, while [[augur]]s were trusted with taking the [[auspice]]s. The [[sacred king]] took on the religious responsibilities of the deposed kings. |

| − | + | As contact with the [[Ancient Greece|Greeks]] increased, the old Roman gods became increasingly associated with Greek gods. Thus, [[Jupiter (god)|Jupiter]] was perceived to be the same deity as [[Zeus]], [[Mars (god)|Mars]] became associated with [[Ares]], and Neptune with [[Poseidon]]. The Roman gods also assumed the attributes and mythologies of these Greek gods. The transferral of [[anthropomorphism|anthropomorphic]] qualities to Roman Gods, and the prevalence of Greek philosophy among well-educated Romans, brought about an increasing neglect of the old rites, and in the [[1st century BC]], the religious importance of the old priestly offices declined rapidly, though their civic importance and political influence remained. Roman religion in the empire tended more and more to center on the imperial house, and several emperors were deified after their deaths. | |

| − | + | Under the empire, numerous foreign cults grew popular, such as the worship of the Egyptian [[Isis]] and the [[Iran|Persian]] [[Mithras]]. Beginning in the 2nd century, [[Christianity]] began to spread in the Empire, despite initial persecution. It became an officially supported religion in the Roman state under [[Constantine I (emperor)|Constantine I]], and all religions except Christianity were prohibited in [[391]] by an edict of Emperor [[Theodosius I]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Technology== |

| − | + | [[image:RomanAbacusRecon.jpg|right|framed|The [[Roman abacus]], the first portable calculating device, helped speed up the use of [[Roman arithmetic]].]] | |

| − | + | Ancient Rome boasted the most impressive technological feats of its day, utilizing many advancements that would be lost in the [[Middle Ages]] and not be rivaled again until the [[19th century|19th]] and [[20th century|20th centuries]]. However, though adept at adopting and synthesizing other cultures' technologies, the Roman civilization was not especially innovative or progressive. The development of new ideas was rarely encouraged; Roman society considered the articulate soldier who could wisely govern a large household the ideal, and [[Roman law]] made no provisions for [[intellectual property]] or the promotion of invention. The concept of "scientists" and "engineers" did not yet exist, and advancements were often divided based on craft, with groups of [[artisan]]s jealously guarding new technologies as [[trade secret]]s. Nevertheless, a number of vital technological breakthroughs were spread and thoroughly utilized by Rome, contributing to an enormous degree to Rome's dominance and lasting influence in Europe. | |

| + | <!--Add paragraphs on Roman calendar, numerals and counting system, etc. here. Possibly some info on Roman boats, though Rome's navy can be addressed under "Military". --> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Engineering and architecture=== |

| − | + | [[Image:Pont du gard.jpg|left|thumb|250px|[[Pont du Gard]] in [[France]] is a Roman aqueduct built in ca. [[19 BC]]. It is one of France's top tourist attractions and a [[World Heritage Site]].]] | |

| − | {{ | + | {{main|Roman engineering|Roman architecture}} |

| − | + | Roman engineering constituted a large portion of Rome's technological superiority and legacy, and contributed to the construction of hundreds of roads, bridges, aqueducts, baths, theaters and arenas. Many monuments, such as the [[Colosseum]], [[Pont du Gard]], and [[Pantheon, Rome|Pantheon]], still remain as testaments to Roman engineering and culture. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The Romans were particularly renowned for [[Roman architecture|their architecture]], which is grouped with Greek traditions into "[[Classical architecture]]". However, for the course of the Roman Republic, Roman architecture remained stylistically almost identical to [[architecture of Ancient Greece|Greek architecture]]. Although there were many differences between Roman and Greek building types, Rome borrowed heavily from Greece in adhering to strict, formulaic building designs and proportions. Aside from two new [[classical order|orders]] of columns, [[composite order|composite]] and [[Tuscan order|Tuscan]], and from the [[dome]], which was derived from the [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscan]] [[arch]], Rome had relatively few architectural innovations until the end of the Roman Republic. |

| − | + | It was at this time, in the [[1st century BC]], that Romans developed [[concrete]], a powerful [[cement]] derived from [[pozzolana]] which soon supplanted [[marble]] as the chief Roman building material and allowed for numerous daring architectural schemata. Also in the 1st century BC, [[Vitruvius]] wrote ''[[De architectura]]'', possibly the first complete treatise on architecture in history. In the late [[1st century]], Rome also began to make use of [[glassblowing]] soon after its invention in [[Syria]], and [[mosaic]]s took the Empire by storm after samples were retrieved during [[Lucius Cornelius Sulla|Sulla]]'s campaigns in Greece. | |

| − | + | [[Image:RomaViaAppiaAntica03.JPG|right|thumb|250px|The [[Appian Way]] (''Via Appia''), a road connecting the city of [[Rome]] to the southern parts of [[Italy]], remains usable even today.]] | |

| − | + | Concrete made possible the paved, durable [[Roman road]]s, many of which were still in use a thousand years after the fall of Rome. The construction of a vast and efficient travel network throughout the Roman Empire dramatically increased Rome's power and influence. Originally constructed for military purposes, to allow [[Roman legion]]s to be rapidly deployed, these highways had enormous economic significance, solidifying Rome's role as a trading crossroads—the origin of the phrase "all roads lead to Rome". The Roman government maintained way stations which provided refreshments to travelers at regular intervials along the roads, constructed bridges where necessary, and established a system of horse relays for couriers that allowed a dispatch to travel up to 800 km (500 miles) in 24 hours. | |

| − | {{ | + | The Romans constructed numerous [[aqueduct]]s to supply water to cities and industrial sites and to assist in [[Roman agriculture|their agriculture]]. The city of Rome itself was supplied by eleven aqueducts with a combined length of 350 km (260 miles).{{ref|frontinus}} Most aqueducts were constructed below the surface, with only small portions above ground supported by arches. Powered entirely by [[gravity]], the aqueducts transported very large amounts of water with an efficiency that remained unsurpassed for two thousand years. Sometimes, where depressions deeper than 50 miles had to be crossed, [[inverted siphon]]s were used to force water uphill.{{ref|waterhistory}} |

| − | + | The Romans also made major advancements in sanitation. Romans were particularly famous for their public [[bathing|baths]], called ''[[thermae]]'', which were used for both hygienic and social purposes. Many Roman houses came to have [[flush toilet]]s and [[domestic water system|indoor plumbing]], and a complex [[sewer]] system, the [[Cloaca Maxima]], was used to drain the local marshes and carry waste into the River [[Tiber]]. However, some historians have speculated that the use of lead pipes in sewer and plumbing systems led to widespread [[lead poisoning]] which contributed to the decline in birth rate and general decay of Roman society leading up to the [[decline of the Roman Empire|fall of Rome]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | '' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Military== | ==Military== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Cornicen on Trajan's column.JPG|thumb|right|300px|Roman soldiers on the cast of Trajan's column in the Victoria and Albert museum, London.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | The early Roman army was, like those of other contemporary city-states, a citizen force | + | The early Roman army was, like those of other contemporary city-states, a citizen force in which the bulk of the troops fought as [[hoplite]]s. The soldiers were required to supply their own arms and they returned to civilian life once their service was ended. |

The first of the great army reformers, [[Camillus]], reorganized the army to adopt [[maniple (military unit)|manipular]] tactics and divided the infantry into three lines: ''[[hastati]]'', ''[[principes]]'' and ''[[triarii]]''. | The first of the great army reformers, [[Camillus]], reorganized the army to adopt [[maniple (military unit)|manipular]] tactics and divided the infantry into three lines: ''[[hastati]]'', ''[[principes]]'' and ''[[triarii]]''. | ||

| − | The middle class smallholders had traditionally been the backbone of the Roman army but | + | The middle class smallholders had traditionally been the backbone of the Roman army, but by the end of the [[2nd century BCE]], the self-owning farmer had largely disappeared as a social class. Faced with acute manpower problems, [[Gaius Marius]] transformed the army into a fully professional force and accepted recruits from the lower classes. |

| − | The | + | The [[Roman legion]] was one of the strongest aspects of the Roman army. The [[Roman triumph]] was a civic ceremony and religious rite held to publicly honor a military commander. |

| − | + | The last army reorganization came when Emperor [[Constantine I]] divided the army into a static defense force and a mobile field army. During the Late Empire, Rome also became increasingly dependent on allied contingents, ''[[foederati]]''. | |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | + | ||

*[[List of Ancient Rome-related topics]] | *[[List of Ancient Rome-related topics]] | ||

*[[Timeline of Ancient Rome]] | *[[Timeline of Ancient Rome]] | ||

| + | *[[Roman agriculture]] | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.crystalinks.com/rome.html Ancient Rome info] | *[http://www.crystalinks.com/rome.html Ancient Rome info] | ||

| − | *[http://www.exovedate.com/ancient_timeline_one.html Ancient Roman | + | *[http://www.exovedate.com/ancient_timeline_one.html Ancient Roman History Timeline] |

*[http://www.historylink101.com/ancient_rome.htm Ancient Rome pictures, art, and info] | *[http://www.historylink101.com/ancient_rome.htm Ancient Rome pictures, art, and info] | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.forumromanum.org/life/johnston_intro.html ''The Private Life of the Romans'' by [[Harold Whetstone Johnston]]] | |

| − | [[ | ||

Latest revision as of 07:03, 1 October 2009

Ancient Rome was a civilization that grew out of the city-state of Rome, founded on the Italian peninsula in the 8th century BCE. During its twelve-century existence, the Roman civilization shifted from a monarchy to an oligarchic republic to a vast empire. It came to dominate Western Europe and the entire area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea through conquest and assimilation, but eventually succumbed to barbarian invasions in the 5th century, marking the decline of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

The Roman civilization is often grouped into "classical antiquity" with ancient Greece, a civilization that inspired much of the culture of ancient Rome. Ancient Rome contributed heavily to the development of law, war, art, literature, architecture, and language in the Western world, and its history continues to have a major influence on the world today.

History

Main Article History of Rome and Timeline of ancient Rome

Monarchy

Main Article Roman Kingdom

The city of Rome grew from settlements around a ford on the river Tiber, a crossroads of traffic and trade. According to archaeological evidence, the village of Rome was probably founded sometime in the 9th century BC by members of two central Italian tribes, the Latins and the Sabines, on the Palatine and Quirinal Hills. The Etruscans, who had previously settled to the north in Etruria, seem to have established political control in the region by the late 7th century BC. The Etruscans apparently lost power in the area by the late 6th century BC, and at this point, the original Latin and Sabine tribes reinvented their government by creating a republic, with much greater restraints on the ability of rulers to exercise power.

In Roman legend, Rome was founded on April 21, 753 BC by twins descendents of the Trojan prince Aeneas, Romulus and Remus. Romulus, whose name inspired the name Rome, killed Remus in a quarrel over where their new city would be located, and became the first of seven Kings of Rome.

Republic

The Roman Republic was established around 510 BC, according to later writers such as Livy, when the last of the seven king of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed, and a system based on annually-elected magistrates was established. The most important magistrates were the two consuls, who together exercised executive authority, but had to contend with the Senate, which grew in size and power with the establishment of the Republic. The magistracies were originally restricted to the elite patricians, but were later opened to common people, or plebs.

The Romans gradually subdued the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the Etruscans. The last threat to Roman hegemony in Italy came when Tarentum, a major Greek colony, enlisted the aid of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 282 BC, but this effort failed as well. The Romans secured their conquests by founding Roman colonies in strategic areas, and established stable control over the region. In the second half of the 3rd century BC, Rome clashed with Carthage in the first two Punic wars. These wars resulted in Rome's first overseas conquests, of Sicily and Hispania, and the rise of Rome as a significant imperial power. After defeating the Macedonian and Seleucid Empires in the 2nd century BC, the Romans became the masters of the Mediterranean Sea.

But foreign dominance led to internal strife. Senators became rich at the provinces' expense, but soldiers, mostly small farmers, were away from home longer and could not maintain their land, and the increased reliance on foreign slaves reduced the availablility of paid work. The Senate squabbled perpetually, repeatedly blocking important land reforms. Violent gangs of the urban unemployed, controlled by rival Senators, intimidated the electorate by violence. The denial of Roman citizenship to allied Italian cities led to the Social War of 91-88 BC. The military reforms of Marius resulted in soldiers often having more loyalty to their commander than to the city, and a powerful general could hold the city and Senate ransom. This culminated in Sulla's brutal dictatorship of 81-79 BC.

In the mid-1st century BC, three men, Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus, formed a secret pact—the First Triumvirate—to control the Republic. After Caesar's conquest of Gaul, a stand-off between Caesar and the Senate led to civil war, with Pompey leading the Senate's forces. Caesar emerged victorious, and was made dictator for life. In 42 BC, Caesar was assassinated by senators fearing that Caesar sought to restore the monarchy, and a Second Triumvirate, consisting of Caesar's designated heir, Augustus, and his former supporters, Mark Antony and Lepidus, took power. However, this alliance too soon descended into a struggle for dominance. Lepidus was exiled, and when Augustus defeated Antony and Cleopatra of Egypt at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, he became the undisputed ruler of Rome.

Empire

With his enemies defeated, Augustus assumed almost absolute power, retaining only the pretense of the Republican form of government. His designated successor, Tiberius, took power without bloodshed, establishing the Julio-Claudian dynasty, which lasted until the death of Nero in 69. The territorial expansion of what was now the Roman Empire continued, and the state remained secure, despite a series of emperors widely viewed as depraved and corrupt. Their rule was followed by the Flavian dynasty. During the reign of the "Five Good Emperors" (96–180), the Empire reached its territorial, economic, and cultural zenith. The state was secure from both internal and external threats, and the Empire prospered during the Pax Romana ("Roman Peace"). With the conquest of Dacia during the reign of Trajan, the Empire reached the peak of its territorial expansion; Rome's dominion now spanned 2.5 million square miles.

The period between 180 and 235 was dominated by the Severan dynasty, and saw several incompetent rulers, such as Elagabalus. This and the increasing influence of the army on imperial succession led to a long period of imperial collapse known as the Crisis of the Third Century. The crisis was ended by the more competent rule of Diocletian, who in 293 divided the Empire into four parts ruled by two co-emperors. The various co-rulers of the Empire competed and fought for supremacy for more than half a century. In 330, Emperor Constantine I moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium, and the Empire was permanently divided into the eastern Byzantine Empire and the Western Roman Empire in 364.

The Western Empire was constantly harassed by barbarian invasions, and the gradual decline of the Roman Empire continued over the centuries. In 410, the city of Rome itself was sacked, and in September 4, 476, the Germanic chief Odoacer forced the last Roman emperor in the west, Romulus Augustus, to abdicate. Having lasted for approximately 1200 years, the rule of Rome in the west came to an end.

Society

Life in ancient Rome revolved around the city of Rome, located on seven hills. The city had a vast number of monumental structures like the Colosseum, the Forum of Trajan and the Pantheon. It had fountains with fresh drinking-water supplied by hundreds of miles of aqueducts, theaters, gymnasium (ancient Greece)s, bath complexes complete with libraries and shops, marketplaces, and functional sewers. Throughout the territory under the control of ancient Rome, residential architecture ranged from very modest houses to country villas, and in the capital city of Rome, there were imperial residences on the elegant Palatine Hill, from which the word "palace" is derived. The poor lived in the city center, packed into apartments, which were almost like modern ghettos.

The city of Rome was the largest urban center of that time, with a population well in excess of one million people, with some high-end estimates of 3.5 million and low-end estimates of 450,000. The public spaces in Rome resounded with such a din of hooves and clatter of iron chariot wheels that Julius Caesar had once proposed a ban on chariot traffic at night. Historical estimates indicate that around 30 percent of population under the jurisdiction of the ancient Rome lived in innumerable urban centers, with population of 10,000 and more and several military settlements, a very high rate of urbanization by pre-industrial standards. Most of these centers had a forum and temples and same type of buildings, on a smaller scale, as found in Rome.

Government

Initially, Rome was ruled by elected kings. The exact nature of the king's power is uncertain; he may have held near-absolute power, or may also have merely been the chief executive of the Senate and the people. At least in military matters, the king's authority (imperium) was likely absolute. He was also the head of the state religion. In addition to the authority of the King, there were three administrative assemblies: the Senate acted as an advisory body for the King, the Curiate Assembly could pass laws suggested by the King, and the Comitia Calata was mainly an assembly of the people to bear witness to certain acts and hear proclamations.

The class struggles of the Roman Republic resulted in an unusual mixture of democracy and oligarchy. Roman laws traditionally could only be passed by a vote of the Popular assembly. Likewise, candidates for public positions had to run for election by the people. However, the Roman Senate represented an oligarchic insitution, which acted as an advisory body. In the Republic, the Senate held great authority (auctoritas), but no actual legislative power (imperium). However, as the senators were individually very influential, it was difficult to accomplish anything against the collective will of the Senate. New Senators were chosen from among the most accomplished citizens by censors, who could also remove a senator from his office if he was found morally corrupt. Later, quaestors were also made automatic members of the Senate.

The Republic had no fixed bureaucracy, and only collected war taxes. Private citizens aspiring to high office largely paid for public works. In order to prevent any citizen from gaining too much power, new magistrates were elected annually and had to share power with a colleague. For example, under normal conditions, the highest authority was held by two consuls. In an emergency, a temporary dictator could be appointed. Throughout the Republic, the administrative system was revised several times to comply with new demands. In the end, it proved inefficient for controlling the ever-expanding dominion of Rome, contributing to the establishment of the Roman Empire.

In the early Empire, the pretense of a republican form of government was maintained: the Roman Emperor was portrayed as only a princeps, or "first citizen", and the Senate retained a degree of influence. However, the rule of the emperors became increasingly autocratic over time, and the Senate was reduced to an advisory body appointed by the emperor. The Empire did not inherit a set bureaucracy from the Republic, since the Republic did not have any permanent governmental structures apart from the Senate. The Emperor appointed assistants and advisors, but the state lacked many institutions, such as a centrally-planned budget. Some historians have cited this as a significant reason for the decline of the Roman Empire.

The territory of the Empire was divided into provinces. The number of provinces increased with time, both as new territories were conquered and as provinces were divided into smaller units to discourage rebellions by powerful local rulers. Initially, the provinces were divided into imperial and senatorial provinces, depending on which institution had the right to select the governor. During the Tetrarchy, the provinces of the empire were divided into 12 dioceses, each headed by a praetor vicarius. The civilian and military authority were separated, with civilian matters still administred by the governor, but with military command transferred to a dux.

Law

The roots to the legal principles and practices of the ancient may be traced to the law of the twelve tables (from 449 BC) to the codification of Emperor Justinian I (around 530). the Roman law as preserved in Justinian's codes became the basis of legal principles and practices in the Byzantine Empire, and in continental Western Europe, and continued, in a broader sense, to be applied throughout most of Europe until the end of the 18th century.

The major divisions of the law of the ancient Rome consisted of Ius Civile, Ius Gentium, and Ius Naturale. The Ius Civile ("Citizen law") was the body of common laws that applied to Roman citizens and the Praetores Urbani (sg. Praetor Urbanus) were the individuals who had jurisdiction over cases involving citizens. The Ius Gentium ("Law of nations") was the body of common laws that applied to foreigners, and their dealings with Roman citizens. The Praetores Peregrini ( sg. Praetor Peregrinus) were the individuals who had jurisdiction over cases involving citizens and foreigners. Ius naturale encompassed natural law, the body of laws that were considered common to all beings.

Economy

Ancient Rome commanded a vast area of land, with tremendous natural and human resources available. As such, Rome's economy remained focused on agriculture and trade. Agricultural free trade changed the Italian landscape, and by the 1st century BC, vast grape and olive estates had supplanted the yeoman farmers, who were unable to match the imported grain price: the annexation of Egypt, Sicily and Tunisia in North Africa provided a continuous supply of grains. In turn, olive oil and wine were Rome's main exports. Two-tier crop rotation was practiced, but farm productivity was overall low, around 1 ton per hectare. Industrial and manufacturing activities were relatively minimal, the largest such activity being the mining and quarrying of stones, which provided basic construction materials for the monuments of that period.

The economy of the early Republic was largely based on smallholding and paid labour, but foreign wars and conquests made slaves increasingly cheap and plentiful, and by the late Republic, the economy was largely dependent on slave labour for both skilled and unskilled work. Slaves are estimated to have constituted around 20% of Rome's population at this time. Only in the later Roman Empire did hired labour became more economical than slave ownership.

Although barter was common in ancient Rome, and often used in tax collection, Rome had a very developed coinage system, with brass, bronze, and precious metal coins in circulation throughout the Empire and beyond—some have even been discovered in India. Before the 3rd century BC, copper was traded by weight, measured in unmarked lumps, across central Italy. The original copper coins (as) had a face value of one Roman pound of copper, but weighed less. Thus, Roman money's utility as a unit of exchange consistently exceeded its intrinsic value as metal; after Nero began debasing the silver denarius, its legal value was an estimated one-third greater than its intrinsic.

Horses were too expensive, and other pack animals too slow, for mass trade on the Roman roads, which connected military posts rather than markets, and were rarely designed for wheels. As a result, there was little transport of commodities between Roman regions until the rise of Roman maritime trade in the 2nd century BC. During that period, a trading vessel took less than a month to complete a trip from Gades to Alexandria via Ostia, spanning the entire length of the Mediterranean. Transport by sea was around 60 times cheaper than by land, so the volume for such trips was much larger.

Class structure

Roman society was strictly hierarchical, with slaves (servi) at the bottom, freedmen (liberti) above them, and free-born citizens at the top. The free citizens were also divided by class. The broadest division was between the patricians, who could trace their ancestry to the founding of the city, and the plebeians, who could not. This became less important in the late Republic, as some plebeian families became wealthy and entered the ranks of the Senate, and some patrician families fell on hard times. In its place, the Roman elite were recognized for either their economic status—the equestrians (equites), wealthy businessmen—or their political status—the nobles (nobiles), who dominated the Senate. To be a noble, an individual needed to have a consul as an ancestor; men like Marius and Cicero, who were the first of their families to rise to the consulship, were given the title novus homo ("new man").

Allied foreign cities were often given the Latin Right, an intermediary level between full citizens and foreigners (peregrini), which gave their citizens rights under Roman law and allowed their leading magistrates to become full Roman citizens. Some of Rome's Italian allies were given full citizenship after the Social War of 91–88 BC, and full Roman citizenship was extended to all free-born men in the Empire by Caracalla in 212.

Family

The basic units of Roman society were households and families. Household included the head of the household (paterfamilias), his wife, children, and other relatives. In the upper classes, slaves and servants were also part of the household. The head of the household had great power (patria potestas, "father's power") over those living with him: He could force marriage and divorce, sell his children into slavery, claim his dependents' property as his own, and possibly even had the right to kill family members, although this has been recently disputed in academic circles.

Patria potestas even extended over adult sons with their own households: A man was not considered a paterfamilias while his own father lived. A daughter, when she married, usually fell under the authority of the paterfamilias of her husband's household, although this was not always the case, as she could choose to continue recognising her father's family as her true family. However, as Romans reckoned descent through the male line, any children she had would belong to her husband's family.

Groups of related households formed a family (gens). Families were based on blood ties (or adoption), but were also political and economic alliances. Especially during the Roman Republic, some powerful families, or Gentes Maiores, came to dominate political life.

Ancient Roman marriage was often regarded more as a financial and political alliance than as a romantic association, especially in the upper classes. Fathers usually began seeking husbands for their daughters when they reached an age between twelve and fourteen. The husband was almost always older than the bride. While upper class girls married very young, there is evidence that lower class women often married in their late teens or early twenties.

Education

The goal of education in Rome was to make the students effective speakers. School started on March 24 each year. Every school day started in the early morning and continued throughout the afternoon. At first, boys were taught to read and write by their father, or by educated slaves, usually of Greek origin. Village schools were also established. Later, around 200 BC, boys and some girls were sent to schools outside the home around age 6. Basic Roman education included reading, writing, and counting, and their materials consisted of scrolls and books. At age 13, students learned about Greek and Roman literature and grammar in school. At age 16, some students went on to rhetoric school. Poorer people did not go to school, but were usually taught by their parents because school was not free.

Language

The native language of the Romans was Latin, an Italic language that relies little on word order, conveying meaning through a system of affixes attached to word stems. Its alphabet, the Latin alphabet, is ultimately based on the Greek alphabet. Although surviving Latin literature consists almost entirely of Classical Latin, an artificial and highly stylized and polished literary language from the 1st century BC, the actual spoken language of the Roman Empire was Vulgar Latin, which significantly differed from Classical Latin in grammar and vocabulary, and eventually in pronunciation.

While Latin remained the main written language of the Roman Empire, Greek came to be the language spoken by the well-educated elite, as most of the literature studied by Romans was written in Greek. In the eastern half of the Roman Empire, which became the Byzantine Empire, Greek eventually supplanted Latin as both the written and spoken language. The expansion of the Roman Empire spread Latin throughout Europe, and over time Vulgar Latin evolved and dialectized in different locations, gradually shifting into a number of distinct Romance languages.

During the European Middle Ages and Early Modern period, Latin maintained a role as western Europe's lingua franca, an international language of academia and diplomacy. Eventually supplanted in this respect by French in the 19th century and English in the 20th century, Latin continues to see heavy use in religious, legal, and scientific terminology. It has been estimated that 80% of all scholarly English words derive directly or indirectly from Latin.

Although Latin is an extinct language with very few remaining fluent speakers, Ecclesiastical Latin remains the traditional language of the Roman Catholic Church and the official language of Vatican City.

Art, literature and music

Most early Roman painting styles show Etruscan influences, particularly in the practice of political painting. In the 3rd century BC, Greek art taken as booty from wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists. Evidence from the remains at Pompeii shows diverse influence from cultures spanning the Roman world. Portrait sculpture during the period utilized youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism. During the Antonine and Severan periods, more ornate hair and bearding became prevalent, created with deeper cutting and drilling. Advancements were also made in relief sculptures, usually depicting Roman victories.

Roman literature was from its very inception influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest extant works are of historical epics telling the early military history of Rome. As the Republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy.

Games and activities

The ancient city of Rome had a place called Campus, a sort of drill ground for Roman soldiers, which was located near the River Tiber. Later, the Campus became Rome's track and field playground, which even Julius Caesar and Augustus were said to have frequented. Imitating the Campus in Rome, similar grounds were developed in several other urban centers and military settlements.

In the campus, the youth assembled to play and exercise, which included jumping, wrestling, boxing and racing. Riding, throwing, and swimming were also preferred physical activities. In the countryside, pastime also included fishing and hunting. Women did not participate in these activities. Ball-playing was a popular sport, and ancient Romans had several ball games, which included Handball (Expulsim Ludere), field hockey, catch, and some form of Soccer.

Religion

Archaic Roman mythology, at least concerning the gods, was made up not of narratives, but rather of complex interrelations between gods and humans. Unlike in Greek mythology, the gods were not personified, but were vaguely-defined sacred spirits called numina. Romans also believed that every person, place or thing had its own genius, or guardian spirit. During the Roman Republic, Roman religion was organized under a strict system of priestly offices, of which the Pontifex Maximus was the most important. Flamens took care of the cults of various gods, while augurs were trusted with taking the auspices. The sacred king took on the religious responsibilities of the deposed kings.

As contact with the Greeks increased, the old Roman gods became increasingly associated with Greek gods. Thus, Jupiter was perceived to be the same deity as Zeus, Mars became associated with Ares, and Neptune with Poseidon. The Roman gods also assumed the attributes and mythologies of these Greek gods. The transferral of anthropomorphic qualities to Roman Gods, and the prevalence of Greek philosophy among well-educated Romans, brought about an increasing neglect of the old rites, and in the 1st century BC, the religious importance of the old priestly offices declined rapidly, though their civic importance and political influence remained. Roman religion in the empire tended more and more to center on the imperial house, and several emperors were deified after their deaths.

Under the empire, numerous foreign cults grew popular, such as the worship of the Egyptian Isis and the Persian Mithras. Beginning in the 2nd century, Christianity began to spread in the Empire, despite initial persecution. It became an officially supported religion in the Roman state under Constantine I, and all religions except Christianity were prohibited in 391 by an edict of Emperor Theodosius I.

Technology

Ancient Rome boasted the most impressive technological feats of its day, utilizing many advancements that would be lost in the Middle Ages and not be rivaled again until the 19th and 20th centuries. However, though adept at adopting and synthesizing other cultures' technologies, the Roman civilization was not especially innovative or progressive. The development of new ideas was rarely encouraged; Roman society considered the articulate soldier who could wisely govern a large household the ideal, and Roman law made no provisions for intellectual property or the promotion of invention. The concept of "scientists" and "engineers" did not yet exist, and advancements were often divided based on craft, with groups of artisans jealously guarding new technologies as trade secrets. Nevertheless, a number of vital technological breakthroughs were spread and thoroughly utilized by Rome, contributing to an enormous degree to Rome's dominance and lasting influence in Europe.

Engineering and architecture

Roman engineering constituted a large portion of Rome's technological superiority and legacy, and contributed to the construction of hundreds of roads, bridges, aqueducts, baths, theaters and arenas. Many monuments, such as the Colosseum, Pont du Gard, and Pantheon, still remain as testaments to Roman engineering and culture.

The Romans were particularly renowned for their architecture, which is grouped with Greek traditions into "Classical architecture". However, for the course of the Roman Republic, Roman architecture remained stylistically almost identical to Greek architecture. Although there were many differences between Roman and Greek building types, Rome borrowed heavily from Greece in adhering to strict, formulaic building designs and proportions. Aside from two new orders of columns, composite and Tuscan, and from the dome, which was derived from the Etruscan arch, Rome had relatively few architectural innovations until the end of the Roman Republic.

It was at this time, in the 1st century BC, that Romans developed concrete, a powerful cement derived from pozzolana which soon supplanted marble as the chief Roman building material and allowed for numerous daring architectural schemata. Also in the 1st century BC, Vitruvius wrote De architectura, possibly the first complete treatise on architecture in history. In the late 1st century, Rome also began to make use of glassblowing soon after its invention in Syria, and mosaics took the Empire by storm after samples were retrieved during Sulla's campaigns in Greece.

Concrete made possible the paved, durable Roman roads, many of which were still in use a thousand years after the fall of Rome. The construction of a vast and efficient travel network throughout the Roman Empire dramatically increased Rome's power and influence. Originally constructed for military purposes, to allow Roman legions to be rapidly deployed, these highways had enormous economic significance, solidifying Rome's role as a trading crossroads—the origin of the phrase "all roads lead to Rome". The Roman government maintained way stations which provided refreshments to travelers at regular intervials along the roads, constructed bridges where necessary, and established a system of horse relays for couriers that allowed a dispatch to travel up to 800 km (500 miles) in 24 hours.

The Romans constructed numerous aqueducts to supply water to cities and industrial sites and to assist in their agriculture. The city of Rome itself was supplied by eleven aqueducts with a combined length of 350 km (260 miles). Most aqueducts were constructed below the surface, with only small portions above ground supported by arches. Powered entirely by gravity, the aqueducts transported very large amounts of water with an efficiency that remained unsurpassed for two thousand years. Sometimes, where depressions deeper than 50 miles had to be crossed, inverted siphons were used to force water uphill.

The Romans also made major advancements in sanitation. Romans were particularly famous for their public baths, called thermae, which were used for both hygienic and social purposes. Many Roman houses came to have flush toilets and indoor plumbing, and a complex sewer system, the Cloaca Maxima, was used to drain the local marshes and carry waste into the River Tiber. However, some historians have speculated that the use of lead pipes in sewer and plumbing systems led to widespread lead poisoning which contributed to the decline in birth rate and general decay of Roman society leading up to the fall of Rome.

Military

The early Roman army was, like those of other contemporary city-states, a citizen force in which the bulk of the troops fought as hoplites. The soldiers were required to supply their own arms and they returned to civilian life once their service was ended.

The first of the great army reformers, Camillus, reorganized the army to adopt manipular tactics and divided the infantry into three lines: hastati, principes and triarii.

The middle class smallholders had traditionally been the backbone of the Roman army, but by the end of the 2nd century BCE, the self-owning farmer had largely disappeared as a social class. Faced with acute manpower problems, Gaius Marius transformed the army into a fully professional force and accepted recruits from the lower classes.

The Roman legion was one of the strongest aspects of the Roman army. The Roman triumph was a civic ceremony and religious rite held to publicly honor a military commander.

The last army reorganization came when Emperor Constantine I divided the army into a static defense force and a mobile field army. During the Late Empire, Rome also became increasingly dependent on allied contingents, foederati.